Diversity without Division.

Diversity without Division.

INVERSITY™ is the inverse of the word “Diversity,” which has "divide" and "division" at its root. Division is exactly what we see happening when diversity is done poorly — that includes checking a box, wagging a finger or placing blame and shame.

Instead of Diversity, we’re going to talk about INversity. We’re going to talk about the things we have IN common with each other.

Karith Foster Has Been Featured In...

"Her approach allows everyone ‘to make mistakes, say the wrong thing sometimes and be able to correct it.’

‘It’s not about being right or wrong but understanding when bias comes into play.’”

The new york times

INVERSITY is a New Approach to Diversity & Belonging Work.

INVERSITY is a New Approach to Diversity & Belonging Work.

INtentional

INVERSITY™ creates and supports brave environments to hold courageous conversations based on INtentional language, positive psychology and neuroscience.

INclusive

INVERSITY™ takes the "division" out of traditional DEI programming by offering a truly INclusive way to communicate, learn, and create an environment vital to an organization's success.

INtrospective

INVERSITY™ honors, recognizes and celebrates INdividuality and all of the INtrinsic value we bring to the table — our background, our heritage, our identity — without letting those things completely run the show.

INviting

INVERSITY™ training and workshops allow organizations to have conversations about DEI in a less threatening, more INviting, deeper and authentic manner.

IN Common

INVERSITY™ shifts the focus from what separates and divides us to what we have IN common, how we can be inclusive of each other—understanding our value, our worth and our connection to humanity.

INnovative

INVERSITY™ expands the idea of diversity to include diversity of thought and ideas, where diverse voices engage in inclusive discourse, leading to INnovative solutions and meaningful INsights.

What INVERSITY™ is NOT

What INVERSITY™ is NOT

INVERSITY™ is not about ignoring or dismissing issues of bias, conscious or unconscious.

INVERSITY™ is not about promoting a philosophy that perpetuates the “blame or shame” game.

INVERSITY™ certainly does not propagate the narrative of "victims and villains" (that is limited thinking; and one that disempowers those who need empowerment the most).

INVERSITY™ is not about ignoring or dismissing issues of bias, conscious or unconscious.

INVERSITY™ is not about promoting a philosophy that perpetuates the “blame or shame” game.

INVERSITY™ certainly does not propagate the narrative of "victims and villains" (that is limited thinking; and one that disempowers those who need empowerment the most).

INVERSITY™ is about maximizing positive outcomes for everyone participating in the conversation.

Because MAYBE we've been doing DEI all wrong.¹

With traditional DEI training, we've been working from the outside in.

When it comes to behavioral change, the least effective approaches involve fear, guilt or regret.⁴

The best way to change behavior is by working from the INside out.

Experts agree that long-lasting change is most likely when it's self-motivated and

rooted in positive psychology.⁴

Naturally, you’ve heard the old saying, “A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.”

So let’s stop shaming people because it’s not getting us anywhere—and only creates more division. This is exactly why traditional DEI doesn’t work long-term.

INVERSITY™ uniquely works by focusing on what unites

people rather than what divides them.

"We think DEI work is a two-way street when it’s actually a six-lane highway."

Karith Foster

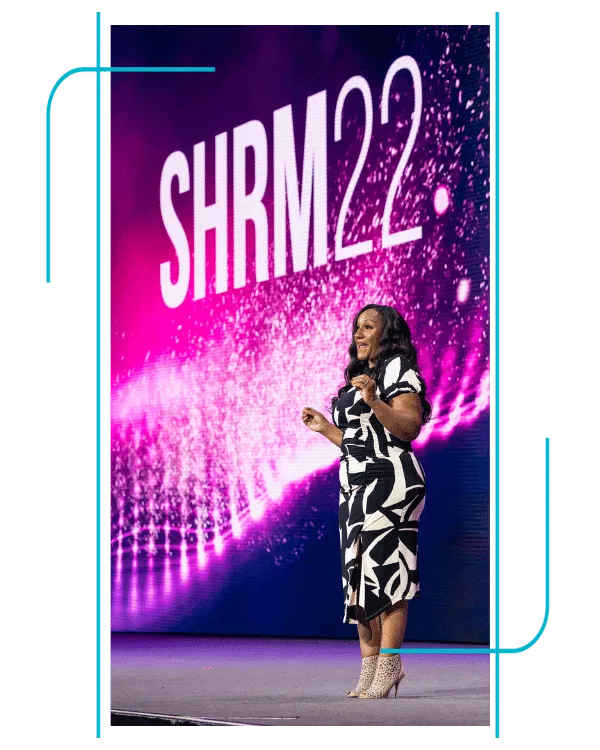

KEYNOTE SPEAKING & WORKSHOPS

For over a decade, Karith has given presentations and training at corporations like The Estée Lauder Companies, Berkshire Hathaway companies, and Bristol-Myer Squibb, academic institutions such as Stanford, MIT, Harvard and training associations like SHRM, CTIA and the US Chamber of Commerce.

LEADERSHIP ROUNDTABLES

Uncover the immense potential of Leadership Roundtables, a collection of dynamic facilitated discussions and planning sessions, equipping leaders to evaluate their progress, advance DEIB efforts and create a C.A.R.E. Culture within their organizations.

ONLINE LEARNING

Access online learning and real tools to navigate the sensitive and ever-evolving landscape of diversity. INVERSITY™ offers seven online learning modules with engaging supplemental activities designed for introspection and reflection.

TESTIMONIALS

What people are saying about INVERSITY™

"Rarely do you find someone both gifted in the art of communication and compassion that even the most controversial and uncomfortable of conversations lose their edge. In place of anger and confusion, Karith masterfully brings peace, calm and resolution

- not to mention the appropriate amount of humor. Her unique and powerful take on DEI is just what the world needs right now."

Susan Scott, Founder, Fierce Conversations

"The traditional approach to diversity and inclusion is in trouble. INVERSITY brings a better approach that has a more significant impact. What is the value of INVERSITY? The top three answers that come to mind are 1. Better collaboration, 2. Enhanced awareness, and 3. Celebration of our uniqueness."

Ibrahim Jackson, CEO & Founder of Ubiquitous Preferred

"Her message of 'inversity,' putting the focus on inclusion rather than division, made a huge impact. The audience enjoyed her presentation style, and fully engaged with her.

Karith’s talk received more enthusiastic positive comments than any other speaker. I was even receiving texts about how great she was while she was still on stage!"

Mark Saum, Principal, Fidelis Consulting Corporation

"Today I had the opportunity to attend your Inversity webinar and I want to thank you for your honesty, transparency, and graciousness.

You shared a piece of your heart in stories that showed vulnerability. Thank you so much for your time and wisdom today."

Linda Lydon, CCWS, Stanford University Human Resources

IT'S NOT HARD WORK;

IT'S HEART WORK.

Footnotes:

* According to 129 studies and a British research group.

1- Diversity training doesn’t work. We’ve been going about DEI all wrong: https://heterodoxacademy.org/blog/diversity-training-doesnt-work-this-might/

2 - Humor is linked to reward processing: http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v4/n3/abs/nn0301_237.html

3 - Dopamine is linked to motivation and long-term memory: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn1406

4 - According to 129 studies and a British research group.

What is INVERSITY™?

INVERSITY™ takes the "division" out of traditional DEI programming by offering a truly INclusive way to communicate, learn, and create an environment vital to an organization's success.

INVERSITY™ accomplishes this mission by creating and supporting brave environments to hold courageous conversations based on intentional language, positive psychology and neuroscience.

Connect on Social

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

INVERSITYTM is a trademark of Inversity Solutions, LLC